SOLO SHOW

JEAN-CLAUDE SILBERMANN

04.09-07.09.25

Avec le soutien aux galeries du CNAP Centre National des arts plastiques / With the support of CNAP Centre National des arts plastiques (National Centre for Visual Arts), France

In a street in Saint-Cirq La Popie, France, Summer 1955

From left to right :

Benjamin Péret, Robert Benayoun, André Breton, Méret Oppenheim, Jean-Claude Silbermann, Marijo Silbermann © Jean-Claude Silbermann’s private collection

Courtesy Jean-Claude Silbermann & galerie Sator

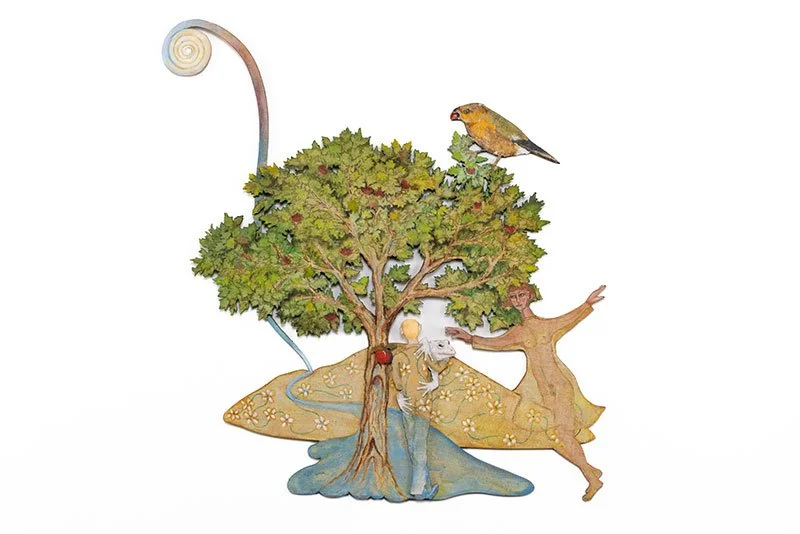

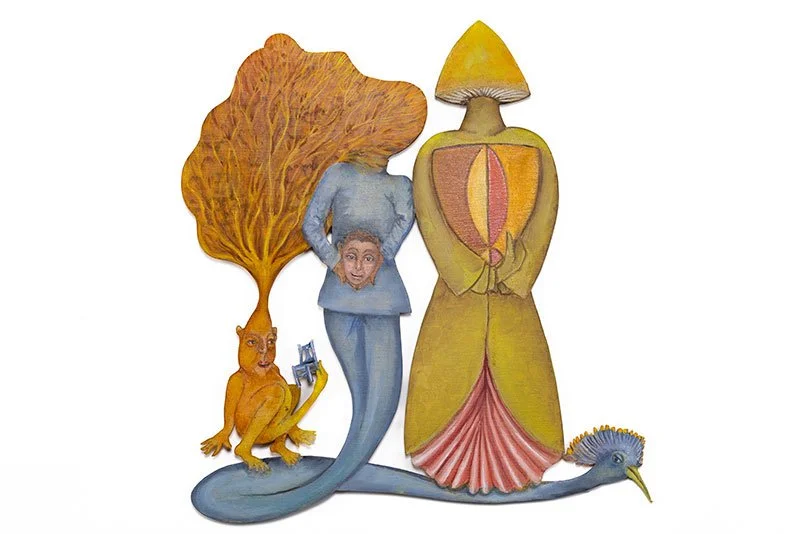

À l'occasion du centenaire du Manifeste du Surréalisme, la galerie Sator présente la première exposition personnelle à New York de l'artiste surréaliste Jean-Claude Silbermann (né en 1935, France). Les peintures découpées de l'artiste nous permettront de nous immerger dans son rapport aux rêves, aux rencontres impromptues et aux hallucinations. Le lien historique avec le surréalisme entre la famille Sator et l'artiste sera mis en évidence.

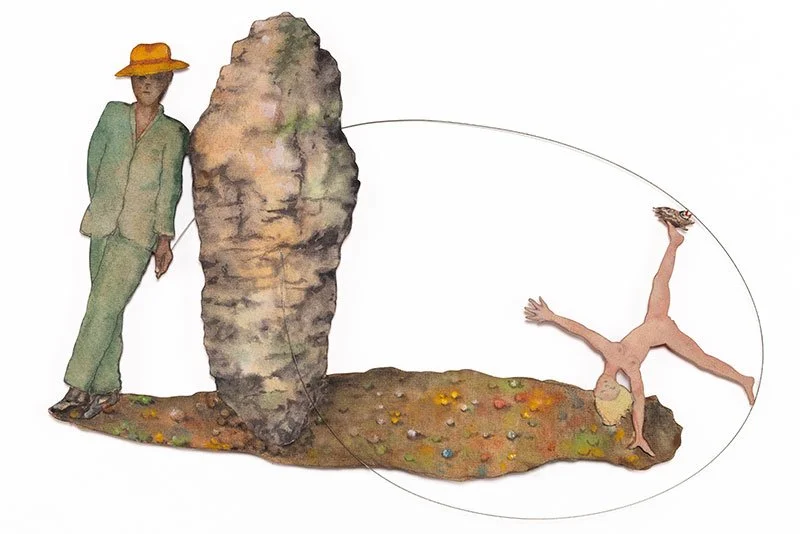

To mark the centenary of the Surrealist Manifesto, galerie Sator presents the first solo show in New York by Surrealist artist Jean-Claude Silbermann (b. 1935, France). The artist’s cut- out paintings will allow us to immerse ourselves in his relationship to dreams, impromptu encounters and hallucinations. The historical link to surrealism between the Sator family and the artist will be highlighted.

Né en 1935 dans une famille bourgeoise, ayant échappé aux persécutions de l’Occupation, il rejoint le groupe surréaliste alors qu’il n’a pas encore 18 ans et participe à ses manifestations jusqu’à sa dissolution après la mort d’André Breton, en 1966. Aussi est-il couramment classé surréaliste. Mais, comme il l’écrit sur le mur d’un couloir, parmi d’autres maximes et observations : « La disparition du groupe surréaliste n’a en rien changé ce que je suis. Pour moi comme pour tous ceux qui s’y sont trouvés embarqués, être surréaliste, c’est être. » Et être, pour lui, c’est créer, c’est-à-dire ne pas savoir ce qui va se passer. Il était ainsi quand il a commencé à chercher, vers 1961. Il en est ainsi aujourd’hui.

Born into a bourgeois family in 1935, having escaped persecution during the Occupation, he joined the Surrealist group before the age of 18 and participated in its events until its dissolution after André Breton’s death in 1966. As a result, he is commonly classified as a Surrealist. But, as he writes on a corridor wall, among other maxims and observations: «The disappearance of the Surrealist group has not changed what I am. For me, as for all those who found themselves embroiled in it, to be a surrealist is to be.» And to be, for him, is to create, which means not knowing what’s going to happen. That’s how he was when he started looking, around 1961. That’s how he is today.

Philippe Dagen, Le Monde, April 2023

L’attente et le moment opportun

Vers la fin du mois d'octobre 2021, je rentrais chez moi en empruntant la petite route bordée d'arbres qui longe la voie ferrée en direction de la gare d'Eaubonne. Il fait nuit. Il n'y a pas de circulation. Je roulais lentement, savourant le rare plaisir de conduire sans précipitation. À quelque deux cents mètres devant moi, sur un petit refuge au croisement de trois rues, j'ai aperçu de dos un homme vêtu de noir qui s'appuyait par l'épaule sur un lampadaire. Il semblait attendre, et j'étais curieux d'assister peut-être à une scène de rencontre. J'ai à peine eu le temps de jeter un coup d'œil sur la rue ouverte par le passage à niveau à ma droite : l'homme s'était volatilisé. Sa disparition a été si rapide que je me suis demandé si je n'avais pas été victime d'une hallucination. Je ne pouvais écarter l'idée qu'en moi ou hors de moi, il attendait la mort - et qu'elle l'avait emporté dans un souffle.

Waiting and the opportune moment

Towards the end of October 2021, I was driving home along the small tree-lined road that runs alongside the railway line towards the Eaubonne station. It was dark. No traffic. I drove slowly, enjoying the rare pleasure of driving without haste. Some two hundred meters ahead of me, on a small refuge at the junction of three streets, I saw from behind a man dressed in black leaning by his shoulder against a lamppost. He seemed to be waiting, and I was curious to perhaps witness a meeting scene. I barely had time to glance at the street opened up by the level crossing to my right: the man had vanished into thin air. His disappearance was so swift that I wondered if I’d been hallucinated. I couldn’t dismiss the idea that inside me or outside me, he was waiting for death - and that it had taken him away in a breath.